In the history of Europe, King Arthur was one of the most important heroic figures although he was simply regarded as a legendary being.

He represents the image of a guardian of old Britain (Wales/ Celts) against the Anglo-Saxon as well as his legend has shown an existential phase of a heroic human being, continuously looking for ultimate power and immortality.

He represents the image of a guardian of old Britain (Wales/ Celts) against the Anglo-Saxon as well as his legend has shown an existential phase of a heroic human being, continuously looking for ultimate power and immortality.

Let's check out the overall story since I am going to explain the role of the King Arthur legend in my novel, Intelligence Code (Part I, Arena of Great Heroes).

The Arthurian Legend

King Arthur

Although there are innumerable variations of the Arthurian legend, the basic story has remained the same. Arthur was the illegitimate son of Uther Pendragon, king of Britain, and Igraine, the wife of Gorlois of Cornwall.

Although there are innumerable variations of the Arthurian legend, the basic story has remained the same. Arthur was the illegitimate son of Uther Pendragon, king of Britain, and Igraine, the wife of Gorlois of Cornwall.

After the death of Uther, Arthur, who had been reared in secrecy, won acknowledgment as king of Britain by successfully withdrawing a sword from a stone.

Merlin, the court magician, then revealed the new king's parentage. Arthur, reigning in his court at Camelot, proved to be a noble king and a mighty warrior. He was the possessor of the miraculous sword Excalibur, given to him by the mysterious Lady of the Lake.

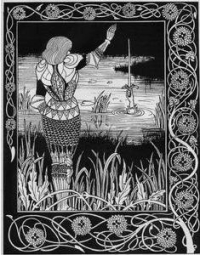

At Arthur's death Sir Bedivere threw Excalibur into the lake; a hand rose from the water, caught the sword, and disappeared.

Another sword, sometimes mistakenly identified with Excalibur, was drawn from a stone by Arthur to prove his royalty.

Knights of the Round Table

Of Arthur's several enemies, the most treacherous were his sister Morgan le Fay and his nephew Mordred. Morgan le Fay was usually represented as an evil sorceress, scheming to win Arthur's throne for herself and her lover. Mordred (or Modred) was variously Arthur's nephew or his son by his sister Morgawse. He seized Arthur's throne during the king's absence. Later he was slain in battle by Arthur, but not before he had fatally wounded the king. Arthur was borne away to the isle of Avalon, where it was expected that he would be healed of his wounds and that he would someday return to his people.

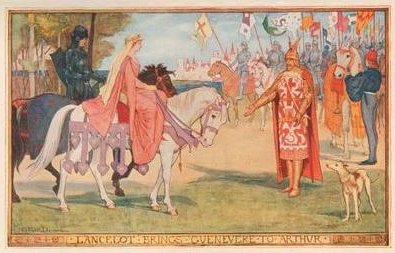

Sir Lancelot and Guinevere

Two of the most invincible knights in Arthur's realm were Sir Tristram and Sir Launcelot of the Lake. Both of them, however, were involved in illicit and tragic love unions - Tristram with Isolde, the queen of Tristram's uncle, King Mark; Launcelot with Guinevere, the queen of his sovereign, King Arthur.

Two of the most invincible knights in Arthur's realm were Sir Tristram and Sir Launcelot of the Lake. Both of them, however, were involved in illicit and tragic love unions - Tristram with Isolde, the queen of Tristram's uncle, King Mark; Launcelot with Guinevere, the queen of his sovereign, King Arthur.

Excalibur

Other knights of importance include the naive Sir Pelleas, who fell helplessly in love with the heartless Ettarre (or Ettard) and Sir Gawain, Arthur's nephew, who appeared variously as the ideal of knightly courtesy and as the bitter enemy of Launcelot.

Other knights of importance include the naive Sir Pelleas, who fell helplessly in love with the heartless Ettarre (or Ettard) and Sir Gawain, Arthur's nephew, who appeared variously as the ideal of knightly courtesy and as the bitter enemy of Launcelot.

Also significant are Sir Balin and Sir Balan, two devoted brothers who unwittingly slew one another; Sir Galahad, Launcelot's son, who was the hero of the quest for the Holy Grail; Sir Kay, Arthur's villainous foster brother; Sir Percivale (or Parsifal); Sir Gareth; Sir Geraint; Sir Bedivere; and other knights of the Round Table.

Round Table

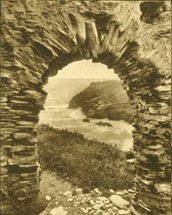

King Arthur's Castle, Tintagel, Cornwall Tintagel, Cornwall

King Arthur's Castle, Tintagel, Cornwall:

tinted view of castle ruins

(postcard by Francis Frith - 1904)

Tintagel, Cornwall:tinted view of the Valley

(postcard by Francis Frith - 1895)

The Link to Celtic Mythology

Formerly, it was thought that the Arthurian legend was the work of several inventive poets and romancers of the Middle Ages. The generally accepted theory now is that Arthurian legend developed out of stories of Celtic mythology. The most archaic form in which these occur in British sources is the Welsh Mabinogion, but much of Irish mythology is palpably identical with Arthurian romance. It is not certain how or where (in Wales or in those parts of northern Britain inhabited by Brythonic-speaking Celts) this legend originated or whether the figure Arthur was based on a historical person.

King Arthur's Castle Doorway

King Arthur's Castle Doorway,

Tintagel, Cornwall (postcard by Francis Frith - 1908)

Tintagel

It is probable that traditional Irish hero stories fused in Britain with those of the Welsh, the Cornish, and the Celts of North Britain. The resultant legend with its hero, Arthur, was transmitted to their Breton cousins on the Continent probably by the year 1000. The Bretons, famous as wandering minstrels, followed Norman armies over Western Europe and used the legend's stories for their repertory. By 1100, therefore, Arthurian stories were well known even in Italy.

Assumptions that a historical Arthur led Welsh resistance to the West Saxon advance from the middle Thames are based on a conflation of two early chroniclers, Gildas and Nennius, and on the Annales Cambriaeof the late 10th century.

The 9th-century Historia Brittonum of Nennius records 12 battles fought by Arthur against the Saxons, culminating in a victory at Mons Badonicus. The Arthurian section of this work, however, is from an undetermined source, possibly a poetic text. The Annales Cambriae also mention Arthur's victory at Mons Badonicus (516) and record the Battle of Camlann (537), "in which Arthur and Medraut fell." Gildas' De excidio et conquestu Britanniae (mid-6th century) implies that Mons Badonicus was fought in about 500 but does not connect it with Arthur.

Another speculative view, put forward by R.G. Collingwood (Roman Britain and the English Settlements, 1936), is that Arthur was a professional soldier, serving the British kings and commanding a cavalry force trained on Roman lines, which he switched from place to place to meet the Saxon threat.

Early Welsh literature, however, quickly made Arthur into a king of wonders and marvels. The 12th-century prose romance Kulhwch and Olwen associated him with other heroes, this conception of a heroic band, with Arthur at its head, doubtless leading to the idea of Arthur's court.

Medieval Sources

The battle of Mt. Badon - in which, according to the Annales Cambriae (c.1150), Arthur carried the Cross of Jesus on his shoulders - but not Arthur’s name, is mentioned (c.540) by Gildas. The earliest apparent mention of Arthur in any known literature is a brief reference to a mighty warrior in the Welsh poem Gododdin (c.600). Arthur next appears in Nennius (c.800) as a Celtic warrior who fought (c.600) 12 victorious battles against the Saxon invaders.

These and several subsequent references indicate that his legend had already developed into a considerable literature before Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his Historia (c.1135), in which he elaborated on the feats of King Arthur whom he represented as the conqueror of Western Europe. After Geoffrey’s Historia came Wace’s Roman de Brut (c.1155), which infused the legend with the spirit of chivalric romance. The Brut (c.1200) of Layamon, modeled on Wace’s work, gives one of the best pictures of Arthur as a national hero.

Chrétien de Troyes, a 12th-century French poet, wrote five romances dealing with the knights of Arthur’s court. His Perceval contains the earliest extant literary version of the quest of the Holy Grail. Two medieval German poets important in the development of Arthurian legend are Wolfram von Eschenbach and Gottfried von Strassburg. The latter’sTristan was the first great literary treatment of the Tristram and Isolde story.

After 1225 no significant medieval Arthurian literature was produced on the Continent. In England, however, the legend continued to flourish. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight(c.1370), one of the best Middle English romances, embodies the ideal of chivalric knighthood.

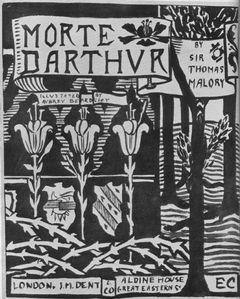

Morte D'Arthur

The last important medieval work dealing with the Arthurian legend is the Morte d’Arthur of Sir Thomas Malory, whose tales have become the source for most subsequent Arthurian material.

The last important medieval work dealing with the Arthurian legend is the Morte d’Arthur of Sir Thomas Malory, whose tales have become the source for most subsequent Arthurian material.

Many writers have used Arthurian themes since Malory, notably Tennyson in his Idylls of the King. Swinburne, William Morris, and Edwin Arlington Robinson also wrote poetic works based on the legend. T. H. White’s trilogy The Once and Future King (1958) is a charming and decidedly 20th-century retelling of the Arthurian story.

[Major Characters]

Merlin, magician, seer, and teacher at the court of King Vortigern and later at the court of King Arthur. He was a bard and culture hero in early Celtic folklore. In Arthurian legend he is famous as a magician and as the counselor of King Arthur. In Tennyson's Idylls of the King Merlin is imprisoned eternally in an old oak tree by the treacherous Vivien (or Nimue), when he reveals the secrets of his knowledge to her.

Lady of the Lake, a misty, supernatural figure endowed with magic powers, who gave the sword Excalibur to King Arthur. She inhabited a castle in an underwater kingdom. According to one legend she kidnapped the infant Launcelot and brought him to her castle where he lived until manhood. She has been identified variously with Morgan le Fay and Vivien. The poem The Lady of the Lake, by Sir Walter Scott, is based on a totally different legend.

Avalon, in Celtic mythology, the blissful otherworld of the dead. In medieval romance it was the island to which the mortally wounded King Arthur was taken, and from which it was expected he would someday return. Avalon is often identified with Glastonbury in Somerset, England.

Guinevere, wife of King Arthur. Her illicit and tragic love for Sir Launcelot, which foreshadowed the downfall of Arthur's kingdom, ends with her retirement to a convent. She also figures in several early romances and Celtic legends, her name appearing in various forms (e.g., Guanhamara, Gvenour, and Gwenhwyfars). In different versions of the Arthurian story her name appears as Guenevere and Guinever.

Sir Launcelot, bravest and most celebrated knight at the court of King Arthur. He was kidnapped as an infant by the mysterious Lady of the Lake, from whom he received his education and took his title, Launcelot of the Lake. As a young man he went to the court of King Arthur, where he was knighted and became one of the most feared warriors in all Christendom. Launcelot was the lover of Guinevere, his sovereign's queen. He was also loved by Elaine (the daughter of King Pelles), by whom he was the father of Sir Galahad, and by Elaine, the Lily Maid of Astolat, who died for love of him. Launcelot's name sometimes appears as Lancelot.

Round Table, the table at which King Arthur and his knights held court. It was allegedly fashioned at the behest of Arthur to prevent quarrels among the knights over precedence. According to one version it was given to Arthur as a wedding gift by his father-in-law. A round table of undetermined antiquity hangs now in the castle at Winchester. Traditionally King Arthur's, it may be a relic of one of the medieval jousts also called round tables.

Chivalry, system of ethical ideals that arose from feudalism and had its highest development in the 12th and 13th centuries. Chivalric ethics originated chiefly in France and Spain and spread rapidly to the rest of the Continent and to England. They represented a fusion of Christian and military concepts of morality and still form the basis of gentlemanly conduct. Noble youths became pages in the castles of other nobles at the age of 7; at 14 they trained as squires in the service of knights, learning horsemanship and military techniques, and were themselves knighted, usually at 21. The chief chivalric virtues were piety, honor, valor, courtesy, chastity, and loyalty. The knight's loyalty was due to the spiritual master, God; to the temporal master, the suzerain; and to the mistress of the heart, his sworn love. Love, in the chivalrous sense, was largely platonic; as a rule, only a virgin or another man's wife could be the chosen object of chivalrous love. With the cult of the Virgin Mary, the relegation of noblewomen to a pedestal reached its highest expression. The ideal of militant knighthood was greatly enhanced by the Crusades. The monastic orders of knighthood, the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitalers, produced soldiers sworn to uphold the Christian ideal. Besides the battlefield, the tournament was the chief arena in which the virtues of chivalry could be proved. The code of chivalrous conduct was worked out with great subtlety in the courts of love that flourished in France and in Flanders. There the most arduous questions of love and honor were argued before the noble ladies who presided (see courtly love). The French military hero Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard, was said to be the last embodiment of the ideals of chivalry. In practice, chivalric conduct was never free from corruption, increasingly evident in the later Middle Ages. Courtly love often deteriorated into promiscuity and adultery and pious militance into barbarous warfare. Moreover, the chivalric duties were not owed to those outside the bounds of feudal obligation. The outward trappings of chivalry and knighthood declined in the 15th century, by which time wars were fought for victory and individual valor was irrelevant. Artificial orders of chivalry, such as the Order of the Golden Fleece (1423), were created by rulers to promote loyalty; tournaments became ritualised, costly, and comparatively bloodless; the traditions of knighthood became obsolete. Medieval secular literature was primarily concerned with knighthood and chivalry. Two masterpieces of this literature are the Chanson de Roland (c.1098; see Roland) and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Arthurian legend and the chansons de geste furnished bases for many later romances and epics. The work of Chrétien de Troyes and the Roman de la Rose also had tremendous influence on European literature. The endless chivalrous and pastoral romances, still widely read in the 16th century, were satirised by Cervantes in Don Quixote. In the 19th century, however, the romantic movement brought about a revival of chivalrous ideals and literature. [See B. E. Broughton, Dictionary of Medieval Knighthood and Chivalry (1986); M. Keen, Chivalry (1984); H. Chickering and T. H. Seiler, ed., The Study of Chivalry (1988).]

---

Lady of the Lake, a misty, supernatural figure endowed with magic powers, who gave the sword Excalibur to King Arthur. She inhabited a castle in an underwater kingdom. According to one legend she kidnapped the infant Launcelot and brought him to her castle where he lived until manhood. She has been identified variously with Morgan le Fay and Vivien. The poem The Lady of the Lake, by Sir Walter Scott, is based on a totally different legend.

Avalon, in Celtic mythology, the blissful otherworld of the dead. In medieval romance it was the island to which the mortally wounded King Arthur was taken, and from which it was expected he would someday return. Avalon is often identified with Glastonbury in Somerset, England.

Guinevere, wife of King Arthur. Her illicit and tragic love for Sir Launcelot, which foreshadowed the downfall of Arthur's kingdom, ends with her retirement to a convent. She also figures in several early romances and Celtic legends, her name appearing in various forms (e.g., Guanhamara, Gvenour, and Gwenhwyfars). In different versions of the Arthurian story her name appears as Guenevere and Guinever.

Sir Launcelot, bravest and most celebrated knight at the court of King Arthur. He was kidnapped as an infant by the mysterious Lady of the Lake, from whom he received his education and took his title, Launcelot of the Lake. As a young man he went to the court of King Arthur, where he was knighted and became one of the most feared warriors in all Christendom. Launcelot was the lover of Guinevere, his sovereign's queen. He was also loved by Elaine (the daughter of King Pelles), by whom he was the father of Sir Galahad, and by Elaine, the Lily Maid of Astolat, who died for love of him. Launcelot's name sometimes appears as Lancelot.

Round Table, the table at which King Arthur and his knights held court. It was allegedly fashioned at the behest of Arthur to prevent quarrels among the knights over precedence. According to one version it was given to Arthur as a wedding gift by his father-in-law. A round table of undetermined antiquity hangs now in the castle at Winchester. Traditionally King Arthur's, it may be a relic of one of the medieval jousts also called round tables.

Chivalry, system of ethical ideals that arose from feudalism and had its highest development in the 12th and 13th centuries. Chivalric ethics originated chiefly in France and Spain and spread rapidly to the rest of the Continent and to England. They represented a fusion of Christian and military concepts of morality and still form the basis of gentlemanly conduct. Noble youths became pages in the castles of other nobles at the age of 7; at 14 they trained as squires in the service of knights, learning horsemanship and military techniques, and were themselves knighted, usually at 21. The chief chivalric virtues were piety, honor, valor, courtesy, chastity, and loyalty. The knight's loyalty was due to the spiritual master, God; to the temporal master, the suzerain; and to the mistress of the heart, his sworn love. Love, in the chivalrous sense, was largely platonic; as a rule, only a virgin or another man's wife could be the chosen object of chivalrous love. With the cult of the Virgin Mary, the relegation of noblewomen to a pedestal reached its highest expression. The ideal of militant knighthood was greatly enhanced by the Crusades. The monastic orders of knighthood, the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitalers, produced soldiers sworn to uphold the Christian ideal. Besides the battlefield, the tournament was the chief arena in which the virtues of chivalry could be proved. The code of chivalrous conduct was worked out with great subtlety in the courts of love that flourished in France and in Flanders. There the most arduous questions of love and honor were argued before the noble ladies who presided (see courtly love). The French military hero Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard, was said to be the last embodiment of the ideals of chivalry. In practice, chivalric conduct was never free from corruption, increasingly evident in the later Middle Ages. Courtly love often deteriorated into promiscuity and adultery and pious militance into barbarous warfare. Moreover, the chivalric duties were not owed to those outside the bounds of feudal obligation. The outward trappings of chivalry and knighthood declined in the 15th century, by which time wars were fought for victory and individual valor was irrelevant. Artificial orders of chivalry, such as the Order of the Golden Fleece (1423), were created by rulers to promote loyalty; tournaments became ritualised, costly, and comparatively bloodless; the traditions of knighthood became obsolete. Medieval secular literature was primarily concerned with knighthood and chivalry. Two masterpieces of this literature are the Chanson de Roland (c.1098; see Roland) and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Arthurian legend and the chansons de geste furnished bases for many later romances and epics. The work of Chrétien de Troyes and the Roman de la Rose also had tremendous influence on European literature. The endless chivalrous and pastoral romances, still widely read in the 16th century, were satirised by Cervantes in Don Quixote. In the 19th century, however, the romantic movement brought about a revival of chivalrous ideals and literature. [See B. E. Broughton, Dictionary of Medieval Knighthood and Chivalry (1986); M. Keen, Chivalry (1984); H. Chickering and T. H. Seiler, ed., The Study of Chivalry (1988).]

---

This article was originally posted at http://www.ramsdale.org/legend.htm.

No comments:

Post a Comment